In Bethesda, Maryland– one of the wealthiest communities in America – some of its residents live at the top and park their cars in a black American cemetery that has existed for over a century.

For decades, white residents of the area were largely unaware of the cemetery’s existence. Yet, although its existence is known today, the city government seems to prefer the truth to remain buried. so he can sell the landincluding the remains of black americansto developers for over $50 million.

A cemetery that was more than a cemetery

In 1911, descendants of former slaves from Maryland built the Moses Macedonia African Cemetery, and since then it has been a vital part of the predominantly black community of Bethesda along River Road.

“The community was a good place to live at that time. We were a big happy community. Everybody loves everybody,” said Harvey Matthews, who grew up on River Road in the 1950s.

Matthews has fond memories of playing hide and seek at the Moses Macedonia African Cemetery, which adjoined his childhood home and was not far from the Macedonian Baptist Church, of which he is still a member. But the threat of racial violence and terror was never far away.

For the black community of River Road, the cemetery had also become their playground as separate public parks were prohibited. Yet by the late 1950s and early 1960s, the tranquility of the black community had been shattered by the growing presence of the Ku Klux Klan, and in just over a decade nearly every trace of the community black had been erased.

In response to the civil rights movement, the 1950s saw the third iteration of the KKK, but unlike the previous two iterations, this version of the KKK was decentralized and hyperlocal. Racist white Americans wore KKK balaclavas and robes and terrorized black communities without the need for centralized organization. Despite the collapse of the KKK in the 1940s, it was reborn a decade later because its racist philosophy of terror still shines among American segregationists.

Matthews’ family left River Road in 1959 to escape the KKK.

“Some of the same Montgomery County police who were supposed to protect you were the same people you saw when you had a spike in the Klansmen at night. We had no one to turn to for help,” Matthews told The Daily Beast. “It was pure hell. You just had to go through that and pray that you wouldn’t lose your life.

A few hundred people gather outside the Baptist Church of Macedonia during a rally and march in an attempt to preserve African American heritage February 12, 2017 in Bethesda, MD.

Katherine Frey/The Washington Post via Getty Images

By the 1960s, after intimidation from the KKK, various government policies that put price tags on black residents, and unscrupulous developers who instigated black people to abandon their land, the black community of River Road was gone. Soon after, the white Marylanders moved in and built Westwood Towers apartments on the African cemetery of Moses Macedonia.

During construction, all the tombstones have been razedthen as the foundations of the apartment complex were being dug, body parts were discovered.

Since the developers had always known they were building on a cemetery, the discovery of dead black bodies was more of an unavoidable nuisance, rather than a deterrent or justification for stopping construction. Instead of moving the bodies or engaging in countless other humanitarian actions, the developers decided to encapsulate the bodies in asphalt and build a parking lot over them.

For more than 50 years, residents of a luxurious apartment complex — where rent can exceed $5,000 a month — have parked their cars and lived atop a black graveyard.

fight for their ancestors

“Right now, every day. Cars park over these bodies,” Steven Lieberman, a partner at Rothwell law firm Figg, told The Daily Beast. “I think most people would agree that’s a profanation.”

Lieberman is representing the descendants of those buried at the Moses Macedonia African Cemetery and other community leaders (including Matthews) in a lawsuit against the Montgomery County Housing Opportunity Commission (HOC) for control of land.

Additionally, her clients have also created a non-profit organization called Bethesda African Cemetery Coalition (BACC) which raises awareness of this American atrocity and fights to preserve the bodies of their ancestors.

“…after KKK intimidation, various government policies that put price tags on black residents, and unscrupulous developers who caused black people to abandon their land, the black community of River Road was gone.”

In August 2021, on behalf of his plaintiffs, Lieberman filed a lawsuit in Maryland Circuit Court to compel the HOC to comply with Maryland laws and not sell Westwood Towers to developers. These Maryland laws require that landowners – before selling cemetery or cemetery land – must obtain court approval to do so. This approval process normally involves hearing the views of the deceased’s representatives, and then the court determines an equitable remedy, which may include blocking the sale.

In this case, the HOC attempted to ignore the law and sell the cemetery to the highest bidder. In the summer of 2021, the HOC accepted a $51 million offer from Charger Ventures LLC and expected to complete the sale in early September 2021, before Lieberman and BACC intervened.

On October 25, 2021, Circuit Court Judge Karla N. Smith confirmed the preliminary injunction to stop the sale, but the HOC appealed the decision and on October 6, 2022, the HOC presented its case to a three-judge panel of the Maryland Special Court of Appeals for overturning the judge’s decision and selling the property. A decision should be announced in the coming months.

An apartment building rises above a parking lot, believed to have been built over an African American cemetery, in Bethesda, MD January 27, 2017. Historians and activists fear the history of the region is literally paved by unbridled development.

Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post via Getty Images

“Justice for us is that the land be transferred back to the descendant community and the land be used to build a museum and a sacred space,” Marsha Coleman-Adebayo, president of the Bethesda African Cemetery Coalition, told The Daily Beast. . . “[The museum and sacred space] would be used to teach future generations about both genocide and the erasure of the community and its culture, and the theft of land from the River Road; as well as the culture, history, achievements and significance of the River Road community.

In her 2021 decision, Justice Smith said, “The Court cannot ignore that the plaintiffs, who are African Americans, seek to preserve the memory of their loved ones and those with whom they share a cultural affiliation. Nor can the Court ignore that as early as the 1930s, when construction began in the River Road community, the deceased were forgotten, abandoned, and their final resting places destroyed or, at a minimum, desecrated.

Following Justice Smith’s ruling, Charger Ventures LLC canceled its plan to purchase Westwood Towers because the deal could not be completed by the agreed date. However, they told the Bethesda Beat in November 2021 that “Charger continues to express strong interest in resuming negotiations to purchase the property”.

According to Lieberman, the HOC makes an “incredibly cruel” argument in this case because it claims that due to the lack of headstones or other records, descendants cannot prove that their ancestors are buried there.

Yet even though descendants could prove their ancestors are in the cemetery, the HOC also argues that descendants cannot prove they are buried on the plot of land that became the Westwood Towers parking lot and, at the instead, their remains could reside on the adjacent properties which include a Starbucks, a Giant Food grocery store, a mall, and a Whole Foods.

Essentially, the HOC is attempting to use the desecration of black bodies and graves from the past, as justification to desecrate them in the present.

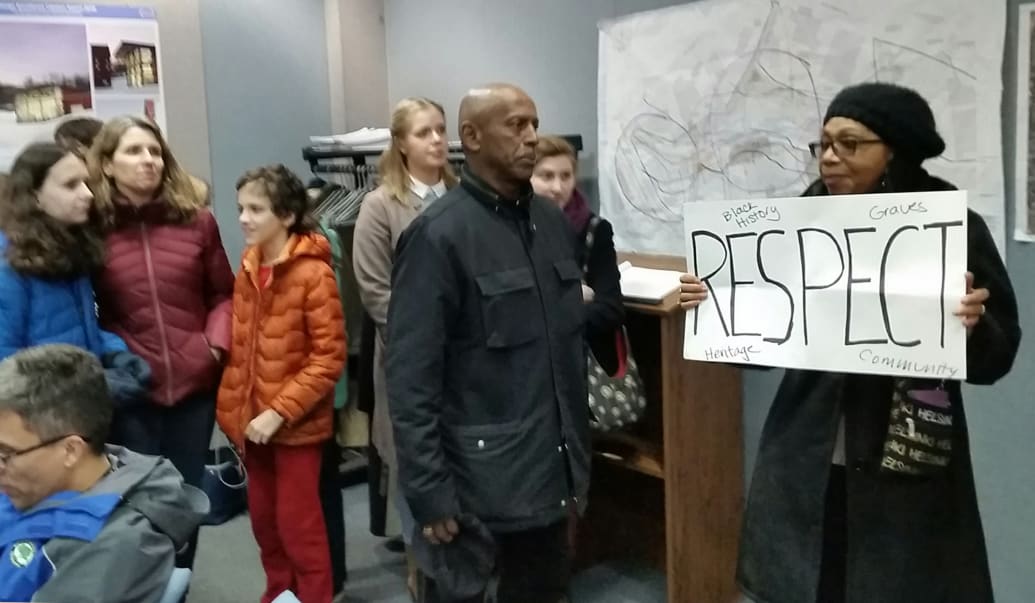

Marsha Coleman-Adebayo holds a protest sign during a Montgomery County Planning Board meeting in Silver Spring, MD on February 16, 2017.

Bill Turk/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Based on this barbaric argument, it is possible that this year a court in Maryland will approve the sale of land housing the remains of hundreds of black Americans in the name of economic growth, gentrification and profit at the expense of residents. Maryland blacks and their ancestors. .

But this court case tells only a fraction of the story of the black residents of River Road and the generational erasure of black life in the name of white wealth.

Maryland still doesn’t reckon with its slavery shame

In the 1800s, River Road was mostly plantations and the land was worked by enslaved Africans. In 1860, nearly 13% of Maryland’s population was enslaved.

Despite being a slave state, Maryland sided with the Union during the Civil War, while continuing to practice slavery. In fact, since the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 specifically referred to the Confederate States, the law did not take effect in Maryland. In 1864, Maryland held a constitutional convention and abolished slavery in its new constitution.

During the 1800s, plantation owners along the River Road created a mass grave where all would dispose of the bodies of enslaved Africans. The location of this mass grave is not far from Westwood Towers and in 2020 it was sold to a developer to create a self-storage facility. Currently it is a large open pit next to a McDonald’s, and the government and developers say they have found no human remains. But members of the BACC insist they have proof that their ancestors are buried there and that many of the remains found in this mass grave are those of children.

River Road continues to tell the story of the normalized displacement, terror, desecration and erasure that often plagues the black American community in the name of white wealth.

From chattel slavery to Jim Crow and up to the present day, the struggle to preserve black life and culture in the face of white wealth and business development continues to plague American society. The black community of River Road tells the story of this struggle and the terror inflicted on black Americans, but even today some Marylanders would rather erase that history and carry on business as usual, while black families are re-traumatized.

“My mother, my father, my grandparents and those who rose to fame before me, they cannot stand there. They fought their fight back then. I’m still here. I am still alive. I have my health and my strength,” Matthews said. “I will fight like hell, as long as I have breath in my body, until this situation is resolved.”

The Daily Beast has contacted Charter Ventures LLC and the Maryland HOC for comment. As of press time, neither party has responded.